A Tale of Two Siblings

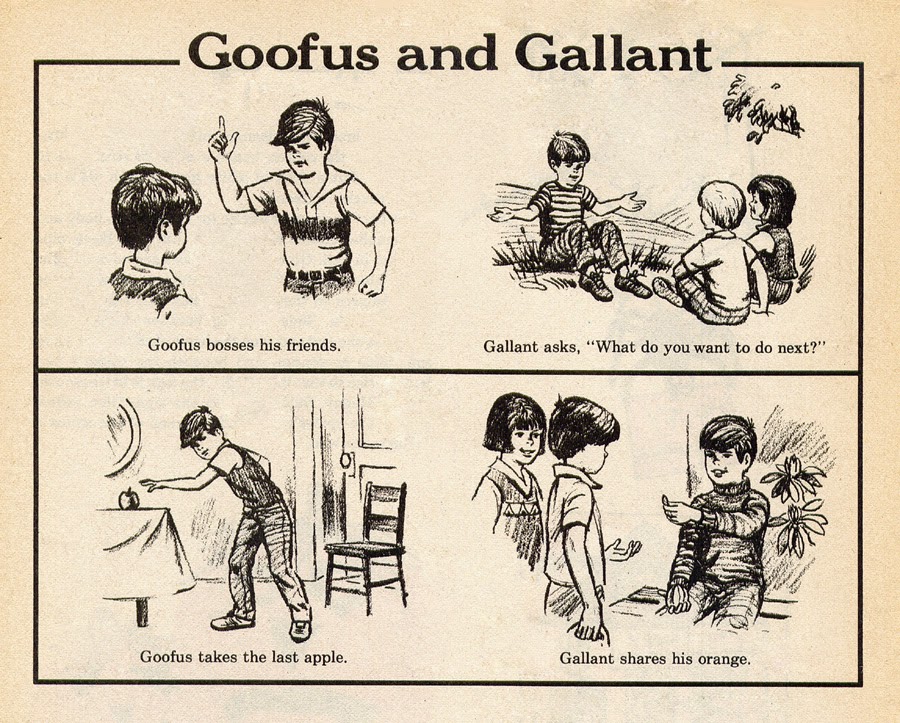

Grief is a terrible child. Happiness and grief are a lot like Goofus and Gallant comic from the children’s magazine Highlights. In the magazine comic, Goofus always does the wrong thing, like eating the whole box of chocolates his grandmother has given him for Valentine’s Day, whereas his twin brother Gallant shares his chocolates with his grandmother, parents, and friends. To make you feel worse, if you are innately more Goofus-like, Gallant would probably offer you the last chocolate in his box, even if he has eaten none of them, even if you have eaten all of yours and are nauseous and vomiting.

Happiness and gratitude are a lot like Gallant. When life is good and your loved ones are alive, your feelings toward them are ever-present but not overwhelming. They are a child that plays quietly in her room while you cook dinner or wash the laundry. When you check on her, she smiles and assures you she’s okay. Sometimes, often, in fact, you seek her out and give her a hug, tell her you love her, but mostly you are content she is there and safe. Your happiness child does not poke you at every opportunity, when you are doing a crossword or driving to the store, to announce “I’m happy! I’m so happy! What should we do about our raging happiness?” Unless you are a manic-depressive and experiencing mania, happiness lives quietly, contently, a warm jacket that you do not even know you are wearing.

When you experience a loss, one’s petulant brat Goofus awakens. He tugs at your shirt while you are making pasta with the Kitchen-Aid, when you are trying to work at home, when you are sitting quietly in a movie theater or concert hall. “I’m sad, I’m so sad. I’m depressed! I’m unhappy!” He whines. “Make me feel better!” He is the baby with colic, the toddler who climbs out of the crib and wanders toward the stairs. You offer Gallant chocolate, the whole box, but he spits it out on the carpet, rubs it on the walls. You hold him but he kicks and scratches you. You try to make him laugh but crocodile tears shine his cheeks and he screams. He cries all night and bothers the neighbors. He won’t put on his clothes in the morning. You take him to the park and he scares the other children. When you ask him what he wants, what will make him feel better, what will placate him, he doesn’t know, only that he’s unhappy and will take it out on you and everyone around you.

You cannot sleep. You cannot concentrate. Your life is a series of reflexes, reactions, trying to anticipate the next outburst, trying to quell the outburst that is happening. You do not think about the future. You cannot indulge your intellectual pursuits. You cannot even feel sorry for yourself. How to keep Goofus alive, safe from self-harm, is your only concern. If you can only get through this day, if you love Goofus and are present with Goofus and give in to Goofus, maybe tomorrow, his raging hunger will be satiated, maybe a little.

But every morning, he shakes you awake. You have been asleep for two hours. He stares at you with his bloodshot, wild eyes. He pulls at your hair.

I am sad! I need! I want!

I will give you anything, Goofus, anything you want. You sit up. Maybe today will be different. What do you want?

I don’t know. I don’t know. He runs downstairs. A crash in the kitchen follows, plates, silverware. You pull yourself out of bed. Did the front door open? Is he going outside, without a coat? Will he dart into traffic? The door slams. Catch him if you can.